We’re reading an excerpt from JRR Tolkien’s “On Fairy Stories” this month, and my guest is Rosamund Hodge, a New York Times-bestselling fantasy author. My favorite of her books is Crimson Bound.

Leah: Tolkien makes the case that fantasy is not childish or limited to children. I’ve certainly reread many of the books I loved as a child, but I’m curious—what’s a work of fantasy you’ve encountered for the first time as an adult and loved, without that love being colored by nostalgia.

Rosamund: I mean… I read A LOT of fantasy, so it's hard to choose one book! But for today, I guess I'll go with The Goblin Emperor by Katharine Addison. It's a book that Tolkien himself might not have considered true Fantasy, because in many ways, it's written like—I was about to say "a historical novel," but really the best comparison I can find is Jane Austen. It's not a story of wonder of the numinous, but it is a story that makes full use of the strangeness of its setting. The hero—whose personality is frankly quite close to Fanny Price—is the unwanted half-Goblin son of the Elven emperor, who has been exiled for all of his short life until an airship disaster claims the lives of his father and all his brothers. Summoned to the capital so he can be crowned emperor, he is forced to learn how to accept/use his new power, while also negotiating around the issues his personal power cannot solve. It's an earnest, hopeful, kind book that refreshes me every time I reread it.

Leah: Kindness is the standout trait of my recommendation, too. I loved Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi (it was on my best books of 2020 list). The protagonist has lost track of his own past, but he has such a tenderness for his world. More heroic stewardship of small things, please!

One of the claims that Tolkien makes is that fantasy is a way to be playful with serious things, comparing it to the work of Lewis Carroll.

For creative Fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun; on a recognition of fact, but not a slavery to it. So upon logic was founded the nonsense that displays itself in the tales and rhymes of Lewis Carroll. If men really could not distinguish between frogs and men, fairy-stories about frog-kings would not have arisen. [...]

And actually fairy-stories deal largely, or (the better ones) mainly, with simple or fundamental things, untouched by Fantasy, but these simplicities are made all the more luminous by their setting. For the story-maker who allows himself to be “free with” Nature can be her lover not her slave. It was in fairy-stories that I first divined the potency of the words, and the wonder of the things, such as stone, and wood, and iron; tree and grass; house and fire; bread and wine.

In your own novels, what do you feel you get to be playful with that you might not get away with in non-genre fiction?

Rosamund: Loath though I am to differ from Tolkien, I have to say that the chance to be "playful" about serious things is not a big part of why I write fantasy. Much more exciting, at least to me, is the chance to be more serious about (certain) serious things than is usual in non-genre fiction. Fantasy allows the literalization—or perhaps I should say incarnation?—of spiritual and philosophical concepts. I get to talk about guilt and sin by branding my heroine with a mark that is changing her from the inside out. I get to talk about the terrifying inevitability of death by creating a city whose enchantments to keep out zombies are slowly failing. And this sort of melodramatic exaggeration actually feels more real to me than a lot of "realistic" fiction. To be Catholic is to believe in a supernatural world more real and important—more beautiful and more terrible—than the everyday "real world" we see around us. Fantasy allows me to express that other dimension of reality, and bring it into the center of a story's action.

Leah: Well, I will accuse you of being playful despite yourself! What I think of, in terms of Tolkien’s use of playfulness, is the playfulness of mathematics. When I’m working to devise a proof, I have to be willing to sit with my axioms, prod them, spin them around a little, shake them very hard like a stuck jukebox, etc.

I love the way fantasy heightens mundane concerns, and sometimes gives us permission to take interest in them again (especially when we feel it’s childish to wonder at the world). This is something I like about dance, too.

Choreography can make it feel like there’s a necessary, causal connection between the partners' movements, even at a distance. In the example above from So You Think You Can Dance, the choreographer wanted to tell a story about drug addiction through the duet. It’s a work of translation.

And a translator has to be playful, to an extent, whether they’re translating from one written language to another, from a lived experience to dance, or from a mundane world to a fantasy one. Everything has to stretch and sea-change to remain true.

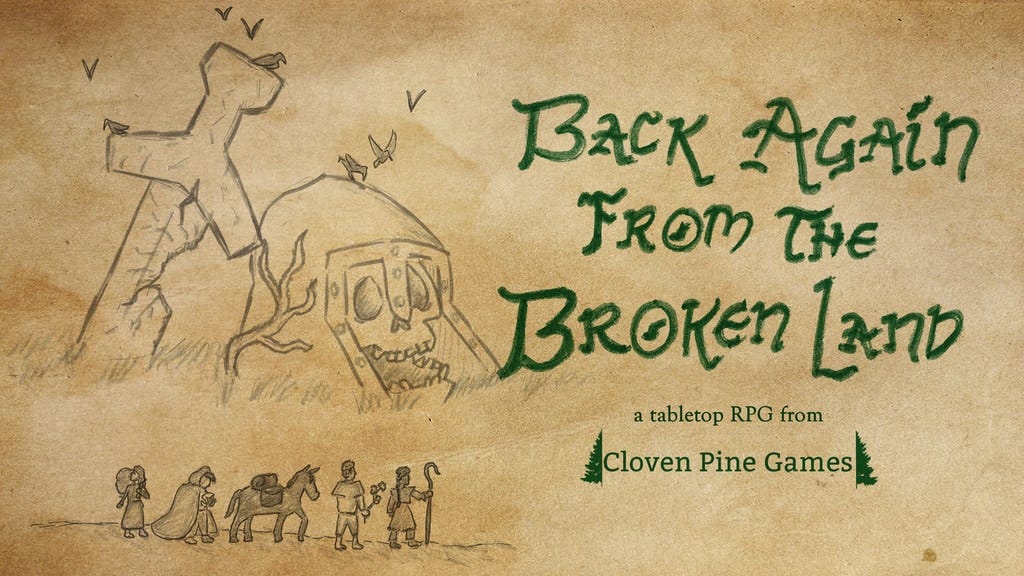

And while we’re talking Tolkien, my husband Alexi and I are kickstarting a Lord of the Rings-inspired game at the beginning of February.

Back Again from the Broken Land is a storytelling game about small adventurers walking home after playing their part in a big war. I’ll share more details when we launch, but you can sign up to learn more on our Kickstarter page. As one of our players said:

What really makes it sing is the way it centres on telling stories: bittersweet, funny, melancholy, and sometimes tense, but always heartfelt.

a book I love as an adult is The Girl Who Drank the Moon! I really recommend it.

This reminds me of "How to Tell a True War Story" in the Things They Carried, and The City & The City by China Mieville and "NK Jemisin's Dream Worlds" in the New Yorker. Like JRR, all three contend that fiction can be more true than what we perceive as reality - that done well it can illuminate and stretch our own abilities to comprehend.

I love this from your excerpt: "It was in fairy-stories that I first divined the potency of the words, and the wonder of the things"- it was through fairy-stories that he understood the truth of words and of the true wonder of the world around him.

The best fiction, I think, breaks and remakes you. Changes you rapidly from your core so that you do not see the world the way you did before you picked up that story. Instead you see it more truly than you did previously, with the blinders you weren't even aware of pulled away. Fantasy has a unique ability to do so by taking you deep into a world where something (or some-things) are flipped on their head, and you can see your whole world from upside down or sideways, perceiving reality in a way you couldn't before...