One Good Graf: The Individual in the Epic

Dana Gioia remembers Robert Fitzgerald

A library hold came in at just the right time. This month, I’ve been reading Studying with Miss Bishop: Memoirs from a Young Writer’s Life, Dana Gioia’s memoir of his teachers. Here’s a paragraph from his chapter on “Remembering Robert Fitzgerald.” (Fitzgerald was a poet in his own right, and a translator of Greek and Latin works).

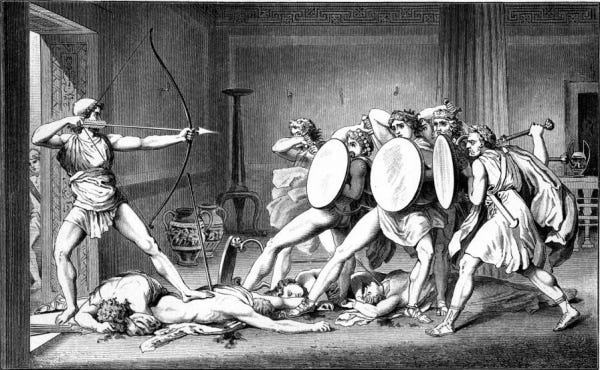

If Fitzgerald believed in teaching details, he also expected us to remember them. He required us to learn every character in each poem. This assignment not only included the major figures, but every soldier, shepherd, sailor, slave, or shade who appeared, even momentarily, from Aietes and Eurymedousa to Medon and Tehoklymenus—hundreds of names and characters. Though we complained at the time, in retrospect, this demand was a clever tactic to teach epic poetry. There is a temptation to read verse narrative as quickly as prose. But narrative poetry is more compressed than prose fiction, and details bear more weight. Fitzgerald slowed down our reading not only by compelling us to take careful notes but also by forcing us to differentiate Ktesippos, Agelaos, Amphimedon, Antinoos, and Eurymakhos from one another—figures we would otherwise have lumped together indiscriminately as Penelope’s suitors. Fitzgerald believed that a great poet never introduced a character without good reason. Our duty was to discover and remember how each figure fit into the whole.

I’ve never read an epic poem this way—I think I received these characters the way I do a big polyphonic work of music. I have a sense of the wall of sound (or characters) and I experience something as they ebb and flow, but I don’t have a strong grasp of their structure or deeper relationship.

I’m looking forward to discussing Gerard Manley Hopkins this month with Holly Ordway, and I enthusiastically recommend Tyler Cowan’s interview with Dana Gioia.